You mean to tell me that the success of the [economic] program and my reelection hinges on the Federal Reserve and a bunch of fucking bond traders?

Only twice before in the last century—after the 1907 Bank Panic and following the 1929 Stock Market Crash—has outrage directed at U.S. financial elites reached today’s level, in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-2009. A Time magazine poll in late October 2009 revealed that 71 percent of the public believed that limits should be imposed on the compensation of Wall Street executives; 67 percent wanted the government to force executive pay cuts on Wall Street firms that received federal bailout money; and 58 percent agreed that Wall Street exerted too much influence over government economic recovery policy.2

In January 2009 President Obama capitalized on the growing anger against financial interests by calling exorbitant bank bonuses subsidized by taxpayer bailouts “shameful,” and threatening new regulations. Journalist Matt Taibbi opened his July 2009 Rolling Stone article with: “The first thing you need to know about Goldman Sachs is that it’s everywhere. The world’s most powerful investment bank is a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money.” Former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund, Simon Johnson, published an article in the May 2009 Atlantic entitled “The Quiet Coup,” decrying the takeover by the “American financial oligarchy” of strategic positions within the federal government that give “the financial sector a veto over public policy.”3

The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, established by Washington in 2009, was charged with examining “the causes, domestic and global, of the current financial and economic crisis in the United States.” Its chairman, Phil Angelides, compared its task to that of the Pecora hearings in the 1930s, which exposed Wall Street’s speculative excesses and malfeasance. The first hearings in January 2010 began with the CEOs of some of the largest U.S. banks: Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley.4

Meanwhile, the federal government has continued its program of salvaging the banks by funneling trillions of dollars in their direction through capital infusions, loan guarantees, subsidies, purchases of toxic waste, etc. This is a time of record bank failures, but also one of rapid financial concentration, as the already “too big to fail firms” at the apex of the financial system are becoming still bigger.

All of this raises the issue of an emerging financial power elite. Has the power of financial interests in U.S. society increased? Has Wall Street’s growing clout affected the U.S. state itself? How is this connected to the present crisis? We will argue that the financialization of U.S. capitalism over the last four decades has been accompanied by a dramatic and probably long-lasting shift in the location of the capitalist class, a growing proportion of which now derives its wealth from finance as opposed to production. This growing dominance of finance can be seen today in the inner corridors of state power.

The Money Trust

Anger over the existence of a “money trust” ruling the U.S. economy reached vast proportions at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth. This was the time when investment bankers midwifed the birth of industrial behemoths, launching the new era of monopoly capital. In return, the investment banks obtained what the Austrian Marxist economist Rudolf Hiferding, in his great work, Financial Capital (1910), called “promoter’s profits.”5 Hilferding and the radical economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen in the United States were the two greatest theorists of the rise of the new age of monopoly capital and financial control. Veblen declared that “the investment bankers collectively are the community custodians of absentee ownership at large, the general staff in charge of the pursuit of business….[T]he banking-houses which have engaged in this enterprise have come in for an effectual controlling interest in the corporations whose financial affairs they administer.”6 In the prototypical merger of the period, the creation in 1901 of the U.S. Steel Corporation, the syndicate of underwriters that J.P. Morgan and Co. put together to float the stock, received 1.3 million shares and over $60 million in commissions, of which J.P. Morgan and Co. got $12 million.7

The 1907 Bank Panic, during which J.P. Morgan himself intervened in the absence of a central bank to stabilize the financial sector, led to the creation in 1913 of the Federal Reserve System, aimed at providing banks with liquidity in a crisis. But it also led to charges, first issued in 1911 by Congressman Charles A. Lindbergh (father of the famous flier), of a “money trust” dominating U.S. finance and industry. Woodrow Wilson, then governor of New Jersey, declared: “The great monopoly in this country is the money monopoly.”

In 1912 an investigation aimed at uncovering the truth behind the money trust issue was launched by the House Committee on Banking and Currency, chaired by Arsene Pujo of Louisiana. The Pujo Committee found that 22 percent of the total banking resources of the nation was concentrated in banks and trust companies based in New York City. It published information showing the lines of financial ownership and control, focusing particularly on J.P. Morgan’s far-flung financial-industrial empire, emphasizing chains of interlocking directorates through which such control was exercised. It pinpointed what it saw as an “inner group” associated with the trio of Morgan at J.P. Morgan and Co., George F. Baker at the First National Bank, and James Stillman at National City Bank, as well as the various other banks and firms they controlled. Collectively, the inner group held three hundred directorships in over one hundred corporations. The Pujo Committee charged that it was not investment but rather control over U.S. finance and industry that was the object of the extensive web of holdings and directorships. It concluded that there was “an established and well-defined identity and community of interest between a few leaders of finance, created and held together through stock ownership, interlocking directorates, partnership and joint account transactions, and other forms of domination over banks, trust companies, railroads, and public-service and industrial corporations, which has resulted in great and rapidly growing concentration of the control of money and credit in the hands of these few men.”

Although, in the end, the Pujo Committee had little effect on Congress, it was to heighten concerns over the money trust and the role of investment bankers. The most searing indictment based on its revelations was provided by Louis Brandeis in Other People’s Money (1913), where he wrote: “The dominant element in our financial oligarchy is the investment banker. Associated banks, trust companies and life insurance companies are his tools….The development of our financial oligarchy followed…lines with which the history of political despotism has familiarized us: usurpation, proceeding by gradual encroachment rather than violent acts, subtle and often long-concealed concentration of distinct functions….It was by processes such as these that Caesar Augustus became master of Rome.”8

The 1929 Stock Market Crash and the Great Depression led again to investigations into the question of the money trust. In his inaugural address, Franklin Roosevelt stated that “the money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization. We may now restore that temple to the ancient truth.” In 1932 the Senate Committee on Banking and Currency began a two-year investigation of the securities markets and of the financial system as a whole, known as the Pecora hearings, after the committee’s dynamic, final chief counsel Ferdinand Pecora. As did the Pujo Committee, the Pecora investigation pointed to the speculative activities of the investment banking affiliates of the major banks. It also singled out interlocking directorates that formed a complex web with its center in a handful of financial interests, of which J.P. Morgan and Co. and Drexel and Co. were especially significant. The Pecora investigation determined that the country was being “placed under the control of financiers.” These hearings led directly to the founding of the Securities and Exchange Commission and to Congress’s passage, within a year, of the Glass-Steagall Act, which required, among other things, the separation of commercial and investment banking. The popular sentiment at the time was perhaps best summed up by Representative Charles Truax of Ohio who declared in relation to the 1934 Securities Exchange Act, “I am for this bill, because it will do something to the bloodiest band of racketeers and vampires that ever sucked the blood of humanity.”9

The Age of Boring Banking

The period after the Great Depression and up to the 1970s has been referred to by Paul Krugman as the era of “boring banking”: “The banking industry that emerged from that collapse [in the 1930s] was tightly regulated, far less colorful than it had been before the Depression, and far less lucrative for those who ran it. Banking became boring, partly because banks were so conservative. Household debt, which had fallen sharply as a percentage of G.D.P. during the Depression and World War II, stayed far below pre-1930s levels.”10 In the 1960s the relative power of the financial sector in U.S. capitalism declined. Investment banking, which had been so important in its heyday in the opening decades of the twentieth century, declined in power and influence.

The regulation of finance associated with Glass-Steagall and with the Securities and Exchange Act is often given credit for the era of “boring banking.” In reality, however, the relative financial stability in these years, and the shift away from financial control exercised by banks, had much more to do with the massive growth of the giant industrial corporations, in what has been called “the golden age” of post-Second World War capitalism. Such giant corporate entities produced enormous economic surpluses and were able to fund their expansion, for the most part, based on their own internal finances. John Kenneth Galbraith stated in American Capitalism (1952): “As the banker, as a symbol of economic power, passed into the shadows his place was taken by the giant industrial corporation.”11 Yet it would be more accurate to say that what emerged after the 1920s was the “coalescence,” under monopoly capitalism, of financial and industrial capital, as suggested by both Lenin and Veblen.12

The Financialization Era13

The last few decades, since the 1970s, and particularly since the 1980s, have seen the rapid financialization of the U.S. economy and of global capitalism in general, as the system’s center of gravity has shifted from production to finance. Although there have been periodic financial crises, beginning with the Pennsylvania Central Railroad failure in 1970, the state has intervened in each crisis as the lender of last resort, and sought to support the financial system. The result over decades has been the massive growth of a financial system in which a debt squeeze-out never quite occurs, leading to bigger financial crises and more aggressive state interventions. One indication of this failure to wipe out debts forcefully despite repeated credit crunches, and of the resulting growth of the financial pyramid, is the historically unprecedented increase in the share of financial profits (i.e., the profits of financial corporations), rising from 17 percent of total domestic corporate profits in 1960, to a peak of 44 percent in 2002. Although the share of financial profits fell to 27 percent by 2007, on the brink of the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-2009 (partly due to gains in industrial profits in this period), it remained steady as the crisis deepened, and rebounded in the first three quarters of 2009 to 31 percent, well above its pre-crisis level—thanks to the federal bailout (and due to the fact that industrial profits remained mired in recession). (See Chart 1).

Nowadays it is common for economists to present the Great Financial Crisis as just another, if more severe, instance of financial crisis, part of a recurring financial cycle under capitalism.14 However, while there have been many other periods of financial mania and panic in the last century—the most famous being the proverbial “roaring twenties,” which led to the Stock Market Crash of 1929—today’s massive secular shift toward increased financial profits, lasting over decades, is historically unprecedented.15 This represents an inversion of the capitalist economy—what Paul Sweezy referred to in 1997 as “the financialization of the capital accumulation process.” In previous periods of capitalist development, financial bubbles occurred at the peak of the business cycle, reflecting what Marx called the “plethora of money capital” at the height of speculation just preceding a crash. Today, however, financial bubbles are better seen as manifestations of a secular process of financialization, feeding on stagnation rather than prosperity. Speculative expansions serve to stimulate the underlying economy for a time, but lead inevitably to increased financial instability.16

The financial system was thus historically transformed into a casino economy, beginning in the 1970s in response to the reappearance of stagnation tendencies within production—and accelerating every decade thereafter. Following the landmark 1987 Stock Market Crash, some of those who had been following the financial explosion since the beginning of the 1970s (and even earlier), such as Hyman Minsky and Paul Sweezy, argued that the system had undergone a major change, reflecting what Minsky dubbed, “money manager capitalism” and what Sweezy called, “the triumph of financial capital.” More recently, this new phase has been termed “monopoly-finance capital.”17

As financialization proceeded, more and more exotic forms of financial innovation (all kinds of futures, options, derivatives, swaps) arose, along with the growth of a whole shadow banking system, off the balance sheets of the banks. The repeal of Glass-Steagall in 1999, although not a major historical event in itself, symbolized the full extent of the deregulation that had by then largely taken place. The system had become increasingly complex, opaque, and ungovernable. A whole new era of financial conglomerates arose, along with the onset in 2007 of the Great Financial Crisis.

In the public’s pursuit of the money trust in the early twentieth century, the emphasis was never on outright concentration in ownership within finance, since banking was less concentrated than many other industries. Rather, stress was placed on interlocking directorships and various lending practices involving “reciprocity,” through which effective control was thought to be exercised by the money trust centered in a few powerful banks. According to the study, “Interest Groups in the American Economy,” carried out by Paul Sweezy for the New Deal agency, the National Resource Committee (published in its 1939 report, The Structure of the American Economy), the fifty largest banks in the United States on December 31, 1936, held 47.9 percent of the average deposits for all commercial banks in 1936. This was the same (at least on the surface) as in 1990, when the fifty largest bank holding companies in the United States held 48 percent of all domestic deposits.18

However, the late 1980s and early 1990s were widely regarded as a period of crisis in U.S. banking, attributable in part to the fact that U.S. commercial banks were no longer thought to be big enough to compete effectively. This could be seen most dramatically in the diminishing weight of U.S. banks relative to the banks of other advanced capitalist countries. In 1970 the U.S. commercial banks dominated in size (measured by deposits) over the main European and Japanese banks. In that year, the world’s three largest banks were BankAmerica, Citicorp, and Chase Manhattan, all based in the United States. Altogether, the United States accounted for eight of the top twenty world banks. By 1986, the world’s largest bank was Japanese, and only three U.S. banks remained in the top twenty. In terms of market value capitalization, U.S. banks were even worse off; Citicorp had fallen in 1986 to twenty-ninth, internationally, while BankAmerica had fallen off the top fifty list altogether.19

If U.S. banks were being ousted in rank by foreign competitors that were becoming larger faster, reflecting economies of scale in banking, they were also affected by a long-run shift, accelerating, in the financialization era, away from banking and toward other forms of financial intermediation, giving banks a smaller share of the total market. In 1950 the assets of commercial banks represented more than half the total for the eleven major types of financial intermediaries (commercial banks, life insurance companies, private pension funds, savings and loan associations, state and local pension funds, finance companies, mutual funds, casualty insurance companies, money-market funds, savings banks, and credit unions). By 1990 this had dwindled to 32 percent. Although the shift away from banking in financial intermediation may have been overstated by these figures, which did not account for the off-balance sheet activities of banks, the growing displacement of U.S. commercial banks in the financialization era emerged as a major concern.20

All this meant growing weaknesses in banking, with banks increasingly encouraged to “skate on thin ice,” as Harry Magdoff and Sweezy phrased it in the 1970s, relying on low levels of capitalization. It also led to increasing bank failures and mergers from 1990 to 2007 that fed concentration and centralization, as banks sought economies of scale and a “too big to fail” position within the economy (the presumed guarantee of a bailout by the federal government in the event of a crisis). Altogether, the United States saw around 11,500 bank mergers from 1980 to 2005, averaging about 440 mergers per year. Moreover, the size of the mergers rose by leaps and bounds. In January 2004 JPMorgan Chase agreed to buy Bank One, forming a $1.1 trillion dollar bank holding company. Bank of America’s decision to buy FleetBoston in October 2003 resulted in a bank holding company of $1.4 trillion in assets (second, at the time, only to Citigroup with $1.6 trillion in assets).21

Financial concentration only accelerated as a result of the Great Financial Crisis that began in 2007. Record numbers of banks failed, and the biggest firms, the main beneficiaries of the federal bailout, sought safety in increased size, hoping to maintain their “too big to fail” status. Of the fifteen largest U.S. commercial banks in 1991 (Citicorp, BankAmerica, Chase Manhattan, J.P. Morgan, Security Pacific, Chemical Banking Corp, NCNB, Manufacturers Hanover, Bankers Trust, Wells Fargo, First Interstate, First Chicago, Fleet/Norstar, PNC Financial, and First Union—with total assets of $1.153 trillion), only five (Citigroup, Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, and PNC Financial—with total assets of $8.913 trillion) survived as independent entities through the end of 2008. Wall Street investment banks suffered the biggest transformation. In 1988, the leading firms in offerings of corporate debt, mortgage-backed securities, equities, and municipal obligations were Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch, Salomon Brothers, First Boston, Morgan Stanley, Shearson Lehman Brothers, Drexel Burnham Lambert, Prudential-Bache, and Bear Stearns. By the end of 2008, only two of these nine remained independent: Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, both of which had morphed into bank holding companies, bringing them under the federal government’s bailout umbrella.

Indeed, the overall level of financial concentration is much greater than can be seen by looking at the big banks alone, since what has emerged in recent years are financial conglomerates, centered in banking and insurance, and engaged in a wide range of financial transactions that dominate the U.S. economy, including off-balance sheet commitments. The ten largest U.S. financial conglomerates, by 2008, held more than 60 percent of U.S. financial assets, compared to only 10 percent in 1990, creating a condition of financial oligopoly. JPMorgan Chase now holds $1 out of every $10 of bank deposits in the country. So do Bank of America and Wells Fargo. These three banks, plus Citigroup, now issue around one out of every two mortgages and account for two out of every three credit cards. As Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Economy.com states: “The oligopoly has tightened.”22

The Financialization of the Capitalist Class

What has been the effect of financialization, as described above, on the composition of the capitalist class and on power relations in U.S. society? The best empirical data available for ascertaining the changing wealth distribution within the capitalist class has been compiled annually since the early 1980s by Forbes magazine, directed at the so-called “Forbes 400,” i.e., the 400 richest Americans. Although the Forbes 400 in 2007 only accounted for around 2.4 percent of total household wealth and 7 percent of the wealth of the richest 1 percent of Americans, their wealth holdings (at $1.54 trillion) were by no means insignificant, nearly equaling the wealth of the bottom half of the U.S. population, or around 150 million people (at $1.6 trillion). Moreover, the Forbes 400, as the super-elite of the capitalist class, can be seen as representing the “cutting edge,” hence the overall direction, of the ruling capitalist class.23

Forbes 400 data includes information on the primary source of wealth, by industrial sector, of each of the individuals. On the basis of this data, it is therefore possible to ascertain the ascending and descending areas of wealth in the portfolios of the richest Americans. A pioneering attempt in 1990 by James Petras and Christian Davenport to use this data to look at the changing composition of wealth of the richest Americans, during 1983-1988, concluded:

The data from the Forbes 400 show that speculator capitalists have become increasingly dominant in the U.S ruling class, displacing industrial and petroleum capitalists….Moreover, the speculative basis of U.S. capitalism brings greater risk of instability. The biggest winners in recent years have been the financial and real estate sectors—and the impending recession could exacerbate their weaknesses and bring them down along with the major industrial sectors to which they are linked.24

There is now a quarter-century of data available in the Forbes 400 series, which allows us to look at the changing composition of wealth on a much longer basis, and over the critical stage of the financialization of the U.S. economy. In analyzing the Forbes series, we use the historical data reconstructed by Peter W. Bernstein and Annalyn Swan, who, in consultation with the Forbes 400 team of researchers, and utilizing the Forbes data archives, went on to publish in 2007 All the Money in the World: How the Forbes 400 Make—and Spend—Their Fortunes. We supplemented this with later research by the same authors, using the Forbes data, published in the October 8, 2007, issue of Forbes.

The changing structure of Forbes 400 wealth over the twenty-five-year period, from 1982-2007 (in percentages for selected years), is shown in Chart 2. (The 1982 figures, as distinguished from later years, do not include the retail category, which was not originally singled out as an area of wealth, due to its small representation within the Forbes 400 in the early 1980s. Consequently retail fell under “Other.”) In 1982 oil and gas was the primary source of wealth for 22.8 percent of the Forbes 400, with manufacturing second at 15.3 percent. Finance, in contrast, was the primary wealth sector for only 9 percent, with finance and real estate together (both included in FIRE, or finance, insurance, and real estate) representing 24 percent. Only a decade later, in 1992, however, finance had surpassed all other areas, representing the primary source of wealth for 17 percent of the Forbes 400, while finance plus real estate constituted 25 percent. Oil and gas, meanwhile, had shrunk to 8.8 percent. Manufacturing, at 14.8 percent, had largely managed to maintain its overall share, though it was now surpassed by finance, as well as a booming media, entertainment, and communications sector, which had risen to 15.5 percent.

By 2007, at the onset of the Great Financial Crisis, the percentage of the Forbes 400 deriving its main source of wealth from finance had soared to 27.3 percent, while finance and real estate together came to 34 percent, with over a third of the richest 400 Americans now deriving their wealth principally from FIRE. The nearest competitor at this time—technology—accounted for about 10.8 percent of Forbes 400 wealth. Manufacturing had sunk to 9.5 percent, although it now slightly exceeded media/entertainment/communications (9.3 percent). The shift over the quarter-century had been massive. In 1982 manufacturing had exceeded finance as a source of wealth by 6 percentage points. In 2007, the positions had been reversed, with finance exceeding manufacturing by 18 percentage points; while finance plus real estate exceeded manufacturing by 25 points.25

What we could call the “financialization of the capitalist class” in this period is reflected, not just in the growth of financial profits as a percentage of total corporate profits, and in the shift of the primary sources of wealth of the richest Americans from finance to real estate, but also in the increase in executive compensation of the financial sector, relative to other sectors of the economy. As Simon Johnson has noted, “From 1948 to 1982, average compensation in the financial sector ranged between 99 percent and 108 percent of the average for all domestic private industries. By 1983, it shot upward, reaching 181 percent in 2007.” In 1988 the nation’s top ten in executive compensation did not include any CEOs in the finance sector. By 2000 finance accounted for the top two. In 2007 it included four of the top five.26

With respect to both profits and executive compensation, there was therefore a massive shift to finance, with the wealth of the top tier of the capitalist class increasingly coming from the financial sector. It is finance king Warren Buffett, even more than technology king Bill Gates, who most exemplifies the new phase of monopoly-finance capital.

Financialization of the State

The dominance of the capitalist class over the U.S. state is exercised through representatives, or various power elites, drawn directly from the capitalist class itself and from its hangers-on, who come to occupy strategic positions in corporate and government circles. The concept of “the power elite” was introduced in the 1950s by sociologist C. Wright Mills, and was subsequently developed by others, notably G. William Domhoff, author of Who Rules America? For Domhoff, the power elite is “the leadership group or operating arm of the ruling class. It is made up of active, working members of the ruling class and high-level employees in institutions controlled by members of the ruling class.”27 In practice, the notion of a general power elite has often given rise to the consideration of specific elites, reflecting the various segments of the capitalist class (for example, industrial and financial capital) and the different dimensions of the exercise of power (economic, political, military, communications, etc.).

As Paul Mason, economics editor of BBC Newsnight, wrote in his 2009 book Meltdown:

Fortunately, even if it is hard to theorise, the power elite of free-market global capitalism is remarkably easy to describe. Although it looks like a hierarchy, it is in fact a network. At the network’s centre are the people who run banks, insurance companies, investment banks and hedge funds, including those who sit on the boards and those who have passed through them at the highest level. The men who met in the New York Federal Reserve on the 12 September 2008 meltdown would deserve a whole circle of their own in any Venn diagram of modern power….Closely overlapping with this network is the military-diplomatic establishment….Another tight circle comprises those companies in the energy and civil engineering business that have benefitted from marketisation at home and US foreign policy abroad.28

The first element in Mason’s composite description of the power elite under “free-market global capitalism” relates to the financial power elite.29 A critical issue today is the extent to which such financial elements have come to dominate strategic sectors within the U.S. state, reflecting the financialization of the capitalist class—and how this affects the capacity of the state to act in accord with the needs of the public. The influence of financial interests is invariably greatest in the Treasury Department. Andrew Mellon, banker and third richest man in the United States during the early twentieth century, served as Secretary of the Treasury from 1921 to 1932. More recently, Bill Clinton selected as his first Treasury Secretary Goldman Sachs co-chairman Robert Rubin. George W. Bush chose as his third Treasury Secretary Goldman Sachs chairman Henry Paulson.30

In looking at the penetration of the financial elite into the corridors of state power (particularly in those areas where their own special interests are concerned), the Obama administration deserves special scrutiny, since the presidential election occurred in the midst of the Great Financial Crisis, which ushered in what has come to be known as the Great Recession. A bailout of the financial sector was already well under way in the Bush administration, and was to be expanded under the new administration. The choice of officials to address the financial crisis was, therefore, by far the biggest, most pressing issue facing the Obama transition team following the election. It was these officials who would be responsible for running TARP (the Troubled Asset Relief Program). Not since the election of Franklin Roosevelt in 1932 had a similar situation presented itself.

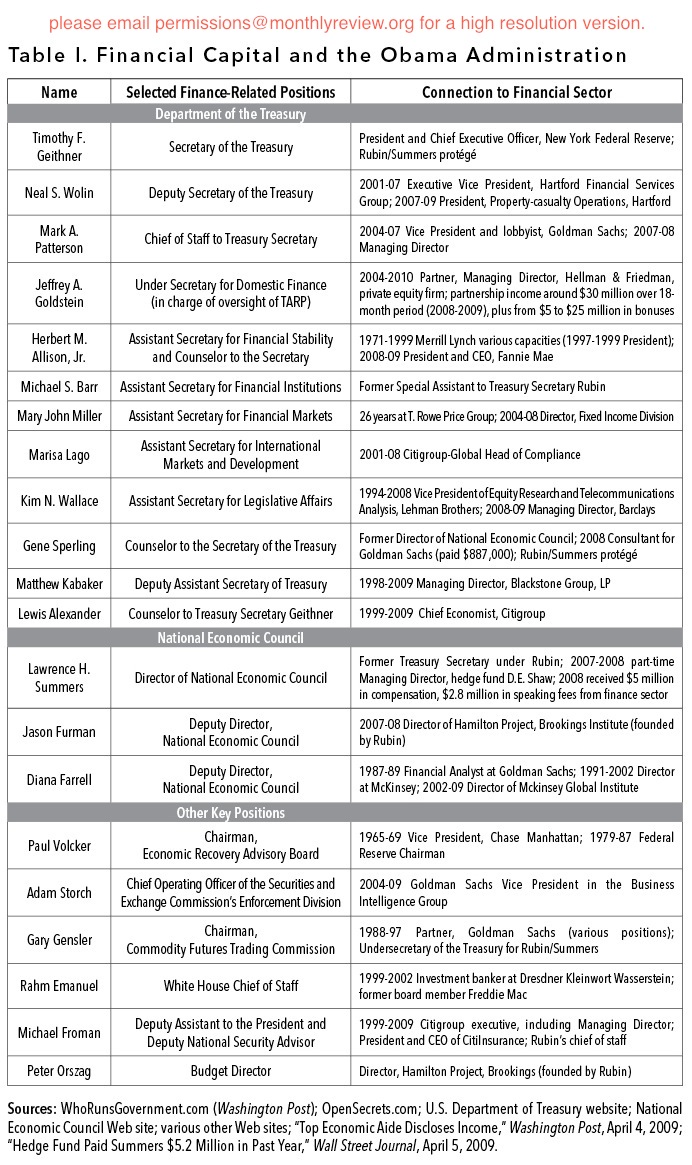

The choices made by the Obama team in this respect are illustrated by Table 1, which presents selected finance-related positions in the administration, and the financial-sector connections of the individuals filling these positions. The results show that the figures who were selected to develop and execute federal policy, with respect to finance, were heavily drawn from executives of financial conglomerates. The evidence also indicates that a tight network exists with numerous links to Goldman Sachs and former Secretary of the Treasury Robert Rubin.

Rubin’s most noteworthy achievement as Treasury Secretary under Clinton was to set the stage for the passage of the 1999 Financial Services Modernization Act (also known as the Gramm-Leach-Bliley bill), which repealed the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933. Rubin resigned in May 1999 and was replaced by his Deputy Secretary Lawrence Summers, now Obama’s chief economic adviser. However, in October 1999, Rubin went on to help broker the final deal on Gramm-Leach-Bliley between the House, Senate and the Clinton administration. A few days after the deal was made, he announced that he had accepted a position as a senior consultant (in the three-person Office of the Chairman) at Citigroup—one of the main beneficiaries of the repeal of Glass-Steagall. In his new job Rubin was granted an annual base salary of $1 million and deferred bonuses for 2000 and 2001 of $14 million annually, plus options in 1999 and 2000 for 1.5 million shares of Citigroup stock. He proceeded to make $126 million in cash and stock over the following decade.

Summers had strongly supported Rubin in this campaign of financial deregulation during the late 1990s bubble, and has himself been well compensated for his efforts. He received $5.2 million in 2008 as a part-time director of the D.E. Shaw hedge fund, and $2.8 million for talks he gave that same year to JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs, and other financial institutions.

Secretary of the Treasury Timothy Geithner, former head of the Federal Reserve of New York, is a Rubin/Summers protégé, as are numerous others in the administration. (Geithner was replaced in 2009 as chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York by William Dudley, who, prior to his selection by the board of directors of the New York Fed—headed by Rubin’s former Goldman Sachs co-chairman, Stephen Friedman—was chief economist, partner, and managing director at Goldman Sachs.) Neal Wolin, up through 2008 a top official of the Hartford insurance conglomerate, now Deputy Secretary of the Treasury under Obama, had, during the Clinton administration, supervised a team of Treasury lawyers responsible for reviewing the legislation repealing Glass-Steagall. Michael Froman, deputy assistant to the president, was Rubin’s chief of staff at Treasury, and followed the latter to Citigroup, where he became a managing director, subsequently joining the Obama administration. He had known Obama from their work together on the Harvard Law Review, and introduced Obama to Rubin.

Obama administration figures charged with financial policy and regulation include former top officers of Citigroup, Chase (now part of JPMorgan Chase), Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch (now part of Bank of America), Lehman Brothers, Barclays, and Hartford Financial, as well as other financial service companies. Hence, in meeting with the administration, representatives of big financial interests frequently find themselves staring across the table at their own former colleagues/executives (and sometimes competitors).31

Although Simon Johnson and others have treated the deep penetration of finance into the Obama administration as a “coup,” it should more properly be viewed as a continuance of the pattern prevalent under previous administrations—though exacerbated by ongoing financialization. Finance is the headquarters of the capitalist class, and the growing importance of the state’s financial role reflects the general financialization of the system in the age of monopoly-finance capital. Today it is no longer the case that finance, as an external force, dominates industry. Rather, industry, which is haunted by conditions of maturity and stagnation, depends on the system of leveraged debt and speculation to stimulate the economy. The coalescence between industry and finance is complete. This is naturally reflected in the capitalist state itself.

The “financialization of the capital accumulation process” has affected the Federal Reserve Board no less than the U.S. Treasury and related government agencies (and their counterparts in the central banks and treasury departments of other leading capitalist nations). The fact that the Fed is charged with being the lender of last resort ultimately puts it in a position of socializing financial losses (while privatizing gains). Today it is widely recognized that, faced with an asset bubble, the capitalist state has little choice but to do what it can to maintain the bubble for as long as possible, and to keep asset prices rising. In a stagnating economy, financialization is the name of the game, and a financial meltdown is conceived as the worst eventuality. Pricking the bubble is seldom considered by the financial authorities, and then never seriously. The job of the Fed in this respect is thus restricted to preventing a bursting bubble from becoming a major meltdown, by speeding to the rescue of speculative capital whenever there is a risk of system-wide instability.

Matters are made more complicated by the existence of the “too big to fail” problem. For financial interests, this provides a strong incentive to merge in order to secure automatic bailout status. This both enhances the profits of firms that are seen as having obtained too big to fail status (giving them “economies of scale” derived from their greater security), and creates what are called “moral hazards,” since such firms are likely to take bigger risks. Coupled with the general drive to financialization, too big to fail generates conditions that threaten to overwhelm the lender of last resort function of the state.32

A further layer of complexity and uncontrollability is added by what Yves Smith, founder of the influential Naked Capitalism financial Web site, has called “the heart of darkness”: the shadow banking system, or black hole of unregulated (and unregulatable) financial innovations, including bank conduits (such as structured investment vehicles), repos, credit default swaps, etc. The system is so opaque and risk-permeated that any restraints imposed threaten to destabilize the whole financial house of cards. At most, the attempt is to prop up the big banks and hope that they will serve as the lynchpins to stabilize the system. Nevertheless, this is made almost impossible, due to the sheer size of the shadow banking system to which the major banks are connected: the off-balance-sheet commitments of the major U.S. commercial banks in 2007 were in the trillions of dollars.33

If all that were not enough, there is the reality that finance is nowadays globalized, with financial transactions no longer subject to the control of any one nation or even group of nations, but increasingly orbiting the globe at record speed. As early as 1982, Magdoff and Sweezy argued that the development of international banking and the international money markets meant that financial crises might develop into a “chain-reaction catastrophe” on a world scale beyond the ability of central banks to intervene effectively.34 The lightning velocity at which financial contagion spread in the current world economic crisis can be taken as an indication of how globalized the financial system and its crises have become.

The U.S. financial lobby, meanwhile, will stop at nothing to ensure that the casino economy is allowed to continue in its present form, without interference or even the slightest concessions. Executive compensation illustrates this point. In 2000-08 Wall Street paid more than $185 billion in bonuses. Before becoming Treasury Secretary, Henry Paulson, in 2005, received a salary of $600,000 as CEO of Goldman Sachs plus $38.2 million in other forms of compensation. In 2008 Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein obtained $1.4 million a week in total compensation ($70.3 million annually). Yet, effective restrictions on executive compensation (salaries, bonuses, stock options, etc.), even in the case of firms receiving taxpayer-funded bailouts, are unlikely.

Chuck Schumer of New York, ranked number three in the Senate Democratic Party leadership, and a key member of two finance committees, was given the job in the new financial reform legislation being debated in Congress of negotiating, on the Democratic Party side, a bipartisan compromise on executive compensation. Schumer is a strong defender of finance, receiving $1.65 million in donations in 2009 from the industry. Nineteen of the twenty-two members of the Senate Banking Committee received donations from Wall Street in 2009. Each of those up for reelection in 2010 are getting at least $180,000. Tony Podesta, the top lobbyist from Bank of America, and Steve Elmendorf, the top lobbyist for Goldman Sachs, both visited the White House six times in 2009. Wall Street gave $14.9 million to Obama’s election campaign, the most for any campaign in history, with Goldman Sachs alone chipping in $1 million.35

Taken together, the foregoing conditions suggest that the emergence of anything on the order of the Pujo and Pecora money trust hearings is extremely improbable today. Despite enormous public outrage, no major new legislation, functionally equivalent to the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, is likely. It is no longer a question of a few New York-based banks controlling large sectors of industrial capital through interlocking directorates. Financialization, understood as a secular process, arising in response to the stagnation of production, increasingly drives the entire system. John Maynard Keynes’s oft-quoted fear that “enterprise” might someday become “the bubble on a whirlpool of speculation” is now a systemic reality.36

The only real option open to humanity under these circumstances, we are convinced, is to scrap the present failed system and to put a new, more rational, egalitarian one its place—one aimed not at the endless pursuit of monetary wealth, but at the satisfaction of genuine human needs.

Notes

- ↩ Clinton quoted in Bob Woodward, The Agenda (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994), 73.

- ↩ Henry Kaufman, The Road to Financial Reformation (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2009), 153; “What’s Still Wrong with Wall Street?” Time Magazine, October 29, 2009, 26.

- ↩ “Obama Calls Wall Street Bonuses “Shameful,” New York Times, January 29, 2009; Matt Taibbi, “The Great American Bubble Machine,” Rolling Stone, July 13, 2009, http://rollingstone.com; Simon Johnson, “The Quiet Coup,” May 2009, http://theatlantic.com.

- ↩ Paul Angelides, “Opening Remarks,” Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, Washington, D.C., September 17, 2009.

- ↩ Rudolf Hilferding, Finance Capital (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1981), 128-29.

- ↩ Thorstein Veblen, Absentee Ownership and Business Enterprise in Recent Times (New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1923), 340-43.

- ↩ Jerry W. Markham, A Financial History of the United States (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 2002), vol. 2, 12-13; Paul M. Sweezy, “Investment Banking Revisited,” Monthly Review 33, no. 10 (March 1982), 6.

- ↩ U.S. House of Representatives, 62nd Congress, Report of the Committee Appointed Pursuant to House Resolutions 429 and 504 to Investigate the Concentration of Control of Money and Credit, February 28, 1913 (Pujo Committee), 55, 129; Markham, A Financial History, vol. 2, 47-54; Louis Brandeis, Other People’s Money (New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co, 1914), 1-4.

- ↩ Markham, A Financial History, vol. 2, 173-86. The most detailed study of the various financial interest groups in the U.S. economy conducted during the New Deal period was “Interest Groups in the American Economy” by Paul M. Sweezy, published as Appendix 13 of Part 1 of the National Resources Committee’s report, The Structure of the American Economy (Washington, 1939). Later reprinted in Paul M. Sweezy, The Present as History (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1953), 158-88.

- ↩ Paul Krugman, “Making Banking Boring,” New York Times, April 9, 2009.

- ↩ John Kenneth Galbraith, American Capitalism (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1953), 108.

- ↩ V.I. Lenin, Imperialism (New York: International Publishers, 1939), 47; Veblen, Absentee Ownership, 227; Paul M. Sweezy and Harry Magdoff, The Dynamics of U.S. Capitalism (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1972), 143.

- ↩ Parts of this section have been adapted from John Bellamy Foster and Hannah Holleman, “The Financialization of the Capitalist Class: Monopoly-Finance Capital and the New Contradictory Relation of Ruling Class Power,” in Henry Veltmeyer, ed., Imperialism, Crisis and Class Struggle: The Enduring Verities and Contemporary Face of Capitalism—Essays in Honour of James Petras (forthcoming, London: Brill, 2010), pp. 163-73.

- ↩ See, for example, Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff, This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009).

- ↩ A clear indication of this is the fact that such disproportionate gains in financial profits relative to other sectors did not occur in the late 1920s prior to the Stock Market Crash. See Solomon Fabricant, “Recent Corporate Profits in the United States,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Bulletin 50 (April 1934), table 2.

- ↩ Paul M. Sweezy, “More (or Less) on Globalization,” Monthly Review 49, no. 4 (September 1997), 3-4; Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 3 (London: Penguin, 1981), 639.

- ↩ Hyman Minsky, “Financial Crises and the Evolution of Capitalism,” in M. Gottdiener and Nicos Kominos, Capitalist Development and Crisis Theory (London: Macmillan, 1989), 391-402; Paul M. Sweezy, “The Triumph of Financial Capital,” Monthly Review 46, no. 2 (June 1994), 1-11; John Bellamy Foster and Fred Magdoff, The Great Financial Crisis (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2009), 63-76.

- ↩ Sweezy, The Present as History, 167; Kenneth J. Stiroh and Jennifer P. Poole, “Explaining the Rising Concentration of Banking Assets in the 1990s,” Federal Reserve Board of New York, Current Issues in Economics and Finance 6, no. 9 (August 2000), 2.

- ↩ Robert E. Litan, What Should Banks Do? (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1987), 126.

- ↩ George G. Kaufman, “The Diminishing Role of Commercial Banking,” in Lawrence H. White, ed., The Crisis in American Banking (New York: New York University Presss, 1993), 143-44.

- ↩ Harry Magdoff and Paul M. Sweezy, The End of Prosperity (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1977), 33-53; Loretta J. Mester, “Some Thoughts on the Evolution of the Banking System and the Process of Financial Intermediation,” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, First and Second Quarters 2007, 67-68.

- ↩ Henry Kaufman, The Road to Financial Reformation (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, 2009), 97-106, 234; Floyd Norris, “To Rein in Pay, Rein in Wall Street,” New York Times, October 30, 2009; David Cho, “Banks ‘Too Big to Fail’ Have Grown Bigger,” Washington Post, August 28, 2009.

- ↩ Arthur B. Kennickell, “Ponds and Streams: Wealth and Income in the U.S., 1989 to 2007,” Federal Reserve Board Working Paper, 2009-13, 2009, 55, 63; Matthew Miller and Duncan Greenburg, ed., “The Richest People in America” (2009), Forbes, September 30, 2009.

- ↩ James Petras and Christian Davenport, “The Changing Wealth of the U.S. Ruling Class,” Monthly Review 42, no. 7 (December 1990), 33-37.

- ↩ The data presented in Chart 2 ends in 2007 at the onset of the Great Financial Crisis. But there has been no change whatsoever in the numbers of those members of the Forbes 400 whose primary wealth is located in finance and real estate between 2007 and 2009. See Matthew Miller, ed., “The Forbes 400” (filtered by industry), Forbes, September 20, 2007; Miller and Greenburg, ed., “The Richest People in America” (2009).

- ↩ Johnson, “The Quiet Coup”; Kevin Phillips, Bad Money (New York: Viking, 2008), 67; “Executive Pay: The Bottom Line at the Top,” New York Times, April 25, 2008.

- ↩ C. Wright Mills, The Power Elite (New York: Oxford University Press, 1956); G. William Domhoff, The Powers That Be (New York: Vintage, 1978), 13. Sweezy objected to Mills’s original tendency to see the corporate rich, the political elite, and the military elite as equal partners of the power elite. If used in this way, the power elite tended to take away from the clarity of the concept of a ruling capitalist class. See Paul M. Sweezy, Modern Capitalism (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1972), 92-109.

- ↩ Paul Mason, Meltdown (London: Verso, 2009), 136-38.

- ↩ Mason excludes other, nonfinancial elements of the corporate rich (e.g. industrial capitalists) from what he describes as the neoliberal power elite because he is himself an advocate of a non-neoliberal, ”rational” capitalism, which would rely on a different power elite—one consisting of what he perceives as these excluded elements.

- ↩ Mark Bearn, “Living the Dream,” New Statesman, December 2006, http://newstatesman.com.

- ↩ Nomi Prins, It Takes a Pillage (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, 2009), 92-95, 140-44; “The Long Demise of Glass-Steagall,” Frontline, Public Broadcasting System, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/wallstreet/weill/demise.html, accessed March 22, 2010; “Former Treasury Secretary Joins Leadership Triangle at Citigroup,” New York Times, October 27, 1999; “Top Economic Aide Discloses Income,” Washington Post, April 4, 2009; “Hedge Fund Paid Summers $5.2 Million in Past Year,” Wall Street Journal, April 5, 2009; “Neal S. Wolin,” WhoRunsGovernment.com. See also Robert Rubin, In an Uncertain World (New York: Random House, 2008), 305-11. Rubin makes a point of excluding the repeal of Glass-Steagall from his memoirs.

- ↩ Gary H. Stern and Ron J. Feldman, Too Big to Fail (Washington, D.C.: Brookings, 2004).

- ↩ Yves Smith, ECONned (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 233-69; Kaufman, 105.

- ↩ Harry Magdoff and Paul M. Sweezy, “Financial Instability: Where Will It All End?” Monthly Review 34, no. 6 (November 1982), 18-23.

- ↩ Prins, It Takes a Pillage, 167-69; “Wall Street Money Rains on Chuck Schumer,” Hedge Fund News, September 29, 2009, http://hedgeco.net; “Keys to Financial Regulation Reform in Senate,” Reuters, March 15, 2010; Timothy P. Carney, “Obama’s Cronies Thrive at Intersection of K and Wall,” WashingtonExaminer.com, February 17, 2010.

- ↩ John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (London: Macmillan, 1973), 159.

Comments are closed.